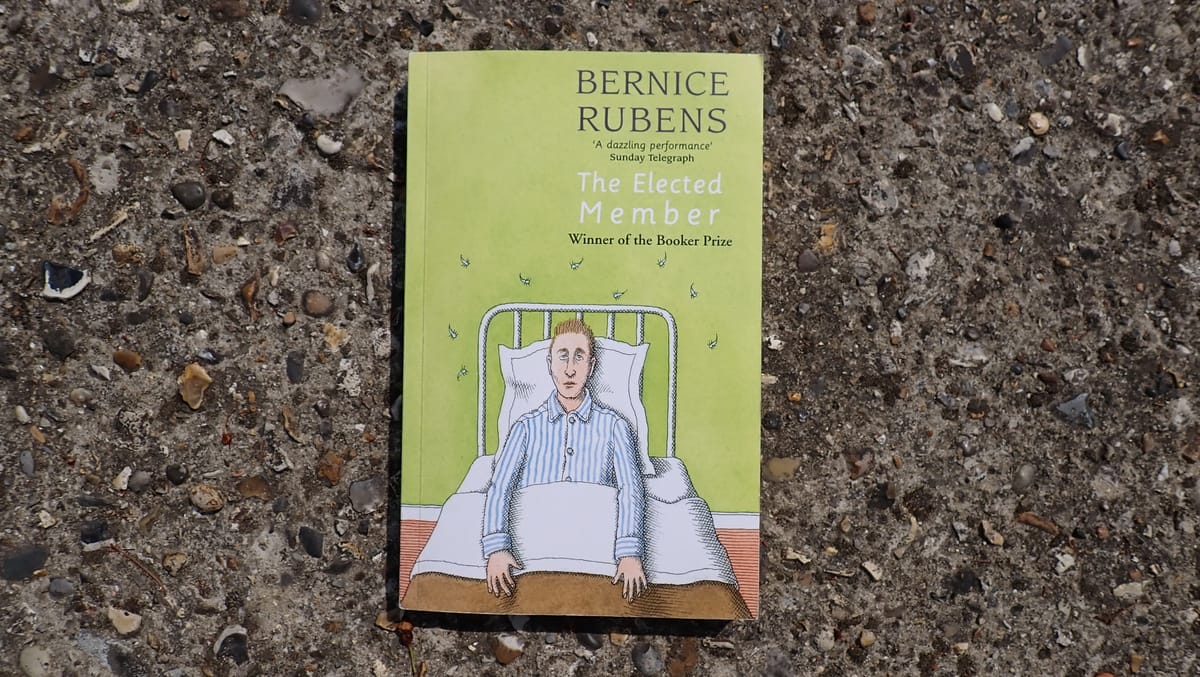

The Elected Member

Bernice Rubens' The Elected Member, winner of the 1970 Booker Prize, is a claustrophobic, darkly comic novel about addiction, family pressure, and identity in an Orthodox Jewish community. A powerful exploration of mental health and cultural expectation, it lingers long after reading.

BERNICE RUBENS

BOOKER PRIZE WINNER 1970

I guess the point of a reading challenge is to push out of your comfort zone and experience self-enforced difference, but sometimes this can lead to odd comforts and deja-vu.

So it was for me with Bernice Rubens' The Elected Member. The story is claustrophic, centred on a single distinct family in a single distinct community within a particular area of London. We're talking here of the East London Orthodox Jewish community (apologies if I have misnamed them here) and it all felt, at least from my point of view, very familiar.

Until 2015 I lived in North East London on the edge of Stamford Hill, the home to just such a community. When looking to buy a flat there more than ten years before we had been hustled out of several viewings by determined members of the community laser focused on moving in amongst their own. They lived parallel lives to us, as if in a parallel universe, with odd quirks for their festivals, for the most part ignoring our presence to the point of appearing to not see us. We loved the quirkiness of it, and when our first child was born, she had a childminder from the local muslim community, a niqab-wearing woman from Oldham, who, when old enough, would take our daughter to and from the local Jewish school (non-orthodox), which had shades of the quirks of the 'uniformed' types we had lived amongst for the years before. The festivals were brilliant. I remember my Anglican school upbringing (I‘m an Atheist) in which everything was so embarassed and half-hearted, even the teachers only walking through the motions. In my daughter's first school, even being 'secular' by Jewish standards' the feast days and holidays were embraced with gusto by everyone (except once by my daughter when she declared 'Mummy I will NOT be a slave', as her and her class mates prepared to be walked out of Egypt).

But we moved more than ten years ago now, out of central London to afford space and a house, and The Elected Member, though set in a slightly different part of the City, brought back not the warm feeling of nostalgia, but a smile of recognition at the claustrophobia and intensity of the focused religious lives that the community chooses to lead.

The story centres around golden-boy Norman, the great intelligent hope of the family and wider community, that he will break out of the intensity of his immediate experience and succeed amongst the gentiles. His impressive intelligence is the pride of everyone connected with the family, but has a darkness attached to it. As a young boy he could perform maths tricks so impressively, that his mother, the lynchpin of the family, decides to 'keep him' at 13 for several years so that he will remain impressive. This of course meant that his older sister Bella, more a housemaid than member of the family, had to be 're-aged' too, with lasting consequences for all.

Norman becomes a barrister and as such has to stick his head above the parapet of life more than in other professions, the family and neighbours come to watch him in the Royal Courts of Justice, but in his forties he becomes a bedbound hallucinating prescription drug addict and everything is broken, particularly after the death of his mother. This is where the book begins.

The family is falling apart, the immigrant orthodox father trying to hold everything together, whilst the spoilt son has gone from saviour to burden, and the invisible Bella, ingored as a human, vainly tries to keep everything together.

As when I read P H Newby's Something to Answer For, I had not previously heard of Bernice Rubens, or any of the 20+ books she published during her life.

Norman gets committed to hospital where he struggles along with others in his ward and slowly the background to his madness is made clear, his best friend and estranged (for that read escaped) eldest sibling, Esther, key to it all.

The book is comic by turns, but underlying is a serious story about mental health, and the struggles of an immigrant community wanting to integrate on their terms, but also hold themselves back, at the same time, within their own, within that which they know.