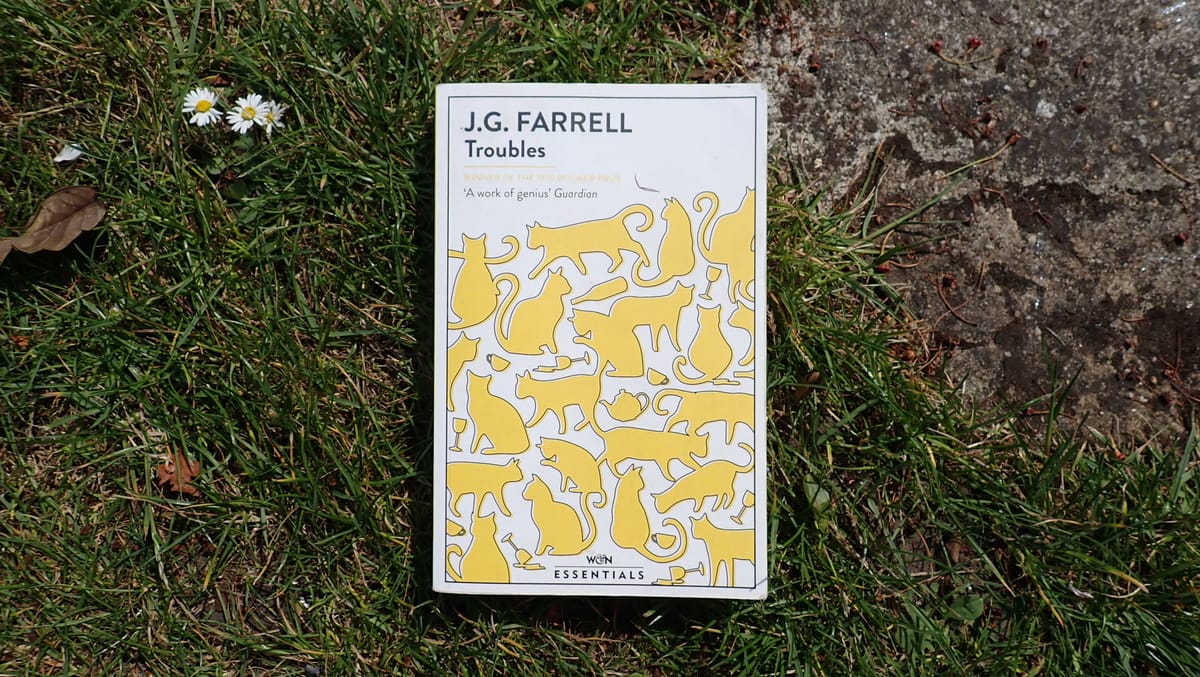

Troubles

A haunting, darkly comic look at English decline and colonial arrogance, Troubles by J.G. Farrell - winner of the 1970 Lost Booker Prize - follows a shell-shocked veteran adrift in a crumbling Irish hotel. A sharp, lyrical novel on empire, trauma and the absurdity of British rule in Ireland.

J G FARRELL

BOOKER PRIZE WINNER 1970 (THE LOST BOOKER)

Troubles won what has become known as the Lost Booker in 1970, making it, posthumously as it were, the second book to win the Booker in 1970, though the prize wasn't awarded until 2010, more than 30 years after J G Farrell's untimely death.

Set on the west coast of Ireland just after the end of the First World War, it's the first of Farrell's Triptych (rather that Trilogy), that deals with the decline of the British Empire, this time at 'home' in Ireland, though clearly neither the British or the Irish would have used that term.

I studied Irish politics in the lead up to independence as part of my first undergraduate degree in Politics and Development Studies, so I was already familiar with the historical context and some of the historical figures that appear, in mention, during the novel.

Firmly focused on disconsolate English bachelor and war veteran Major Brendon Archer, the story opens with his trip to the dilapidated and crumbling Majestic hotel to marry his fiancee, a woman he had met and kissed once on leave during the war, he finds an Anglo-Irish family and hotel in steep decline, endless rooms left to disintegrate, and cats taking over large rooms if not wings of the building.

The Irish servants lessen ever in number and silently watch the decline of the few guests, mainly old women, left as residents, both themselves and the owners living as if it was still the heyday of the hotel, whilst making do to make ends meet; keeping pigs in the squash courts and the like, all the while dismissing the Irish themselves as barbarians and in some sense sub-human. This is, after all, the colonial experience.

Archer sits somehow above all this, an overly passive observer, unable to pull himself away from the palpable decline that he is surrounded by, the careless talk of war and the needless suffering of the Irish whilst he quietly suppresses his PTSD recalling at moments the pieces of his comrades left on the battlefields of France.

Whilst this all might sound terribly grim, there is much comedy here, and the writing is lyrical and builds a wonderful picture of the time and place, but there is an insouciance about the English, and the way they treat the world, the insouciance of the British ruling class, inoculated against the realities of life, observing the starving Irish with passive sadism and a willful misreading of their need to steal crops and so on, in order to eat.

Even in the denouement at the end, the Major seems unable to rouse himself, even at the risk of losing his life, his whole being so infused by ennui following his experience in the trenches and the several years spent at the Majestic watching things fall apart. The finale was an interesting reading experience, the writing such that I didn't feel the seriousness of what was taking place. This was, I felt, deliberate on the part of the author, not a lack of skill.

Overall, this is a great yarn with much to say, and for a tough subject, comical and readable. The English colonials being as laughable as you'd imagine, but unable to see it themselves.